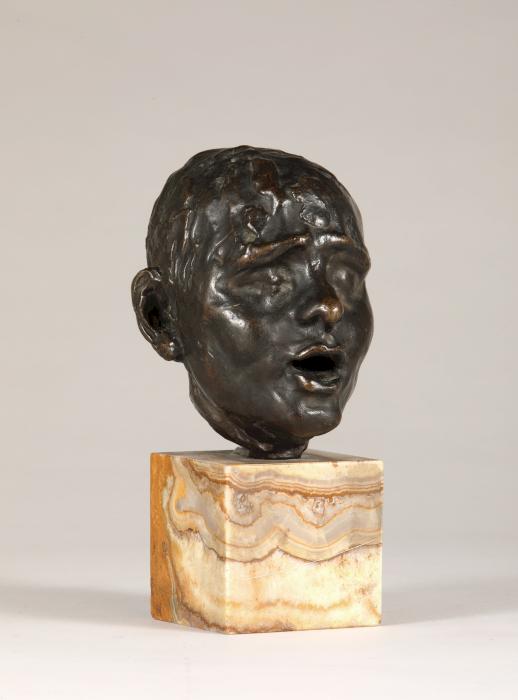

Camille Claudel

Head of a Slave vers 1887

Bronze with brown patina

Sand cast

Signed : “ALEXIS. RUDIER. Fondeur. PARIS”

Signed : “A. Rodin”

12 x 10 x 11 cm

Provenance:

- France, Private Collection

Head of a Slave is one of the works in which Camille Claudel’s and Auguste Rodin’s styles melded. Though it was created for Rodin’s Gates of Hell while Camille Claudel was working as Rodin’s assistant, in the end it was not used in the final version and was never shown. When Rodin died in 1917, the model of Head of a Slave was one of a great many unsigned fragments (heads, hands, feet) found in his studio, and it was included as one of the pieces in the Rodin Museum. In 1990, when a Head of a Slave signed by Camille Claudel appeared, its attribution to Rodin began to be questioned.

A Head of a Slave in terracotta signed “Camille Claudel”

In the second edition of the catalogue raisonné of Camille Claudel’s work, which came out in 1990, Reine-Marie Paris, the artist’s grandniece, included a Head of a Slave in grey terracotta that had just been discovered; it was signed “Camille Claudel” on the neck.[1] It belonged to the collection of Paul and Lucie Audouy, major collectors of the artist and of Symbolist works.[2] Reine-Marie Paris made the connection between their Head of a Slave and the one known through a bronze cast made by the Rodin Museum, which is in the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia.[3] This led her to believe that the work in Philadelphia’s Rodin Museum, despite being signed “A. Rodin,” was actually a piece by Camille Claudel. Furthermore, she suggested that the Philadelphia bronze was evidence that Rodin appropriated Claudel’s work. But while the Head of a Slave can be securely attributed to Camille Claudel, it cannot be proved that Rodin intentionally appropriated her work. In fact, the edition of Head of a Slave was begun after Rodin’s death and was based on one of the plasters of the model held in the museum’s collections. At the time, the director of the Rodin Museum, Georges Grappe, was unaware that Rodin was not, in fact, the artist who created the work, and his signature was added to it in good faith.[4]

The three plasters of Head of a Slave that are held in the Rodin Museum (Inv. S.03902, Inv. S.03951, and Inv. S.04006) appear to have entered the collections in 1916. Plaster S.03951 was used for the sand-cast bronze edition by Alexis Rudier.[5] Plaster S. 4006 may have been used to make other plasters, and plaster S. 3902 is a unique cast.

There are two major differences between the Head of a Slave in grey terracotta signed “Camille Claudel” and the bronze cast described here and signed “A. Rodin.” Other than these two differences, they are identical in every detail.

—The first difference is the cut at the neck; the terracotta emerges from a ball of clay composed of smaller crushed balls with a bulge on the left side where the signature “Camille Claudel” is incised. On the bronze, the clay mass has disappeared, and there is a clean cut at the base of the neck. It seems only natural that Camille Claudel would have kept the signed terracotta for herself, while the plasters left in the studio, which she had made for Rodin, were not signed.

—The second difference is the angle of the head: in the terracotta, the face is tilted back at almost 45 degrees, giving the impression that the person is breathing his last breath, while in the bronze, the face is straight up, facing the viewer and seemingly lost in deep internal meditation.

This change in tilt is easily explained. Though Camille Claudel executed her Head of a Slave with a significant backward tilt, Rodin quite likely planned to use it differently in his Gates. The three remaining plasters are also perfectly vertical. Each one rests on a different base, but in each case, the base holds the head vertically. Such changes in inclination were frequent in Rodin’s and Claudel’s work. For example, the head with eyes closed of Sakuntala that Camille Claudel showed at the Salon of 1888 is titled toward the floor, whereas in The Psalm, it is positioned vertically, facing the viewer.

In 2010, the terracotta of the Head of a Slave entered the municipal collections of the museum at Nogent-sur-Seine (Inv. 2010.1.4); since 2017, it has been shown at the Camille Claudel Museum.

Rodin’s studio and the Gates of Hell

“Character promises to be Mlle Camille Claudel’s strongest quality. In everything that she does, she accentuates the strength and the expression.” Paul Leroi, whose real name was Léon Gauchez, published that comment in 1886, just after he had met Camille Claudel.[6] At the time, the artist was at the very beginning of her career; she had shown work for the first time at the 1885 Salon des Artistes Français. She seems to have joined Rodin’s studio as an assistant around 1884, after he had been her professor in a private studio for young women.

The work that she did in Rodin’s studio is known through her own accounts in letters and through the writings of the art critic Mathias Morhardt.[7] But the archives of the Rodin Museum do not include certain details one would expect to find there. In his article on Claudel, which came out in 1898 in Le Mercure de France, Morhardt remarks that “in the master’s studio, the presence [of Camille Claudel] remains visible in some very interesting fragments.” He refers explicitly to her work on hands and feet but mentions nothing else.[8]

However, as Antoinette Le Normand-Romain emphas, “the representation of the body and facial expressions constitute the essence of Camille Claudel’s work.”[9] In 2005, when she was the head curator of the Rodin Museum, she published, in the exhibition catalogue Claudel and Rodin: Fateful Encounter, some new thoughts on the problems of attribution arising from Camille Claudel having worked for so long in Rodin’s studio.[10] She continued this comparative analysis in 2014, bringing to light the amount of work that Camille Claudel did for the Gates of Hell, the Burghers of Calais, the Balzac, and the Monument to Claude Lorrain.[11] And thus, starting with the 2005 exhibition, institutions began to attribute the Head of a Slave to Camille Claudel. Twenty years later, this attribution has been definitively adopted.[12] As for the date of the Head of a Slave, thoughts on that have also changed over the past twenty years; first dated as “circa 1885,” it is now considered to be “circa 1887.”

From its creation to the present day—a period of more than a century—the title of the Head of a Slave has also gone through changes. In the mid-1920s, when it was first listed in the archives of the Rodin Museum on the occasion of a commission from Jules Mastbaum, the work appeared under the title l’Appel in French and as The Call in English. And yet, fifty years later, in 1976, John L. Tancock, in his reference work on the collection of the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia, used the title Head of a Slave, which he preferred to Head of a Blind Slave. The title Head of a Blind Slavewas given to the work at that time by the Rodin Museum in France.[13] And finally, today, the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia uses the title The Call, while the Rodin Museum in Paris uses Head of a Slave. How can the existence of these different titles be explained? In the context of the Gates of Hell, Rodin might first have planned to position the head in the tympanum, which “was divided into two scenes: on the right of The Thinker ([…] “Dante”), “The Arrival,” a crowd of spirits being pushed toward the banks of the Styx, and on the left, “The Judgement.”[14] Both titles, The Call and Head of a Slave, certainly characterize those damned and enslaved souls, shadows responding to the call to the Last Judgement.[15]

The Style of Head of a Slave

This figure, with its left eye closed and its right eye only half open, signals extreme tension, more emotional than physical. The main subject of Claudel’s Head of a Slave is suffering exhaled through breath. It belongs to the lineage of faces that have marked the history of sculpture, including Michelangelo’s Dying Slave, with its closed eyes, and Bernini’s The Ecstasy of Saint Theresa, with her open mouth. Head of a Slave belongs to a group of figures with closed eyes that Camille Claudel created around this time, such as Louise de Massary (circa 1886, location unknown), Young Woman with Closed Eyes (circa 1885, Poitiers, musée Sainte-Croix, inv. 2000.1), and The Psalm (1888-1893, Abbeville, musée Boucher-de-Perthes, inv. 1893.5.1). While it was still attributed to Rodin, the Head of a Slave could have been compared to his figures with closed eyes, such as Head of Sorrow (1882), Head of a Martyr (1885), and Paolo and Francesca (1887).

According to John L. Tancock, Head of a Slave is based on the same model as Rodin’s The Cry (1898, a study for the marble of the Storm), but Antoinette Le Normand-Romain does not agree.[16] The Head of a Slave does, however, share an intensity of expression with The Cry, even if the force of the latter is more externalized, and the former, more internalized. The treatment of the hair is also the same; a few furrows have been traced in the clay to suggest the strands that frame the face; they catch the light and empha the dramatic dynamic of the face’s expression. These furrows suggesting strands of hair occur often in Claudel’s work, for instance, in the Bust of Léon Lhermitte (1889-1895, Nogent-sur-Seine, Camille Claudel Museum, inv. 2010.3), Head of a Young Woman with a Chignon (circa 1886, Paris, Rodin Museum, inv. S.06729), and Head of Hamadryad (circa 1895, Nogent-sur-Seine, Camille Claudel Museum, inv. 2006.7).

Isolated heads are frequent in Claudel’s work, and often the sculpture for which they were intended is not known. Among them, Study for a Burgher of Calais (circa 1885, Nogent-sur-Seine, Camille Claudel Museum, inv. 2010.1.3) stands in stark contrast to Head of a Slave because of its decisive and firm character, while it also has the same strands of hair deeply traced in the clay.

During the time that Claudel worked in and for Rodin’s studio, her style became so similar to that of the master that it is impossible to tell their work apart.[17] Today, some works can only be attributed to one or the other on the basis of specific documents or signatures on the works themselves. For instance, the Head of Saint John the Baptist and the Head of Avarice, which were once attributed to Camille Claudel, have now been recognized as Rodin’s, while the Head of a Laughing Boy and Head of a Slave, which had been attributed to Rodin are now recognized as Claudel’s. But stylistically speaking, their works had fused, and it is still often very difficult to say definitively which one of them did what. And this is why it remains particularly hard to attribute isolated elements of sculpture for which there is no documentation.

Jules E. Mastbaum’s commission for the first bronzes of Head of a Slave

Jules E. Mastbaum (1872-1926), a manufacturer from Philadelphia who had made his fortune in real estate and cinematography, rapidly became an important collector. Beginning in 1923, he came to Paris to acquire works by Rodin, as he planned to open a museum in Philadelphia dedicated to Rodin’s works.[18] To this end, he gave the Rodin Museum in Paris a number of commissions and chose some works that had never before been cast in bronze editions. “If, as I hope, Mr. Mastbaum is able to appreciate the tremendous and extremely delicate work that these pieces required, please do let him know that these are works by Rodin that have never before been cast in edition, and that they have only ever been seen in his studio by his close friends and a few others aware of his art. So far, no one in the world owns one.”[19] Head of a Slave was among those works that had never left the studio.

In the archives of the Rodin Museum, details of the fourth commission by Jules E. Mastbaum can be found in his letters from 1925 and 1926[20] and in the purchase orders sent to the founder Alexis Rudier.[21] By cross-referencing these documents, it has been established that Alexis Rudier cast only three examples of Head of a Slave for Jules E. Mastbaum and that they were all sent to Philadelphia.[22]

One of these examples was shown in the Sesqui-Centennial International Exhibition, celebrating the signing of the Declaration of Independence, which was held in Philadelphia from June 1 to December 1, 1926; it was included in the exhibition’s catalogue.[23] During the exhibition, Albert Rosenthal, director of the Mastbaum Foundation, wrote to Georges Grappe, saying, “My dear Sir and Friend, I sent you photographs of the Philadelphia Rodin Museum’s exhibition at the Sesqui-Centennial. I thought that they might interest and please you…You might also be pleased to know, my dear friend, that there is an increasing and now substantial interest in Rodin and that our gallery at the Sesqui-Centennial is currently one of the most popular.”[24]

Jules E. Mastbaum died suddenly on December 7, 1926 at the age of 54 and thus did not live to see the opening of the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia. It only opened until three years later, on November 19, 1929, with Paul Claudel attending as French ambassador to the United States. At that time, one of the three casts of Head of a Slave commissioned by Mastbaum already belonged to the museum’s collections; it had been bequeathed to the museum upon the collector’s death (Inv. F1929-7-77).

The different versions of Head of a Slave

As far as is currently known, the extant examples of Head of a Slave include:

—The terracotta in the Camille Claudel Museum in Nogent-sur-Seine[25]

—The three plasters in the Rodin Museum in Paris

—An edition in bronze by the Rodin Museum, which consists of three unnumbered examples cast by Alexis Rudier in the mid-1920s,[26] and a further twelve examples, some numbered, some not, cast by Georges Rudier between 1960 and 1965.[27]

The three signed casts by Alexis Rudier are all known; they are:

—the one in the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia (Inv. F1929-7-77), cast in 1925, which entered their collections through the bequest of Jules E. Mastbaum

—the one presented here

—the one from Jules E. Mastbaum’s personal collection (now in a private collection).

It was mentioned by John L. Tancock in his 1976 work, The Sculpture of Auguste Rodin The Collection of the Rodin Museum Philadelphia.[28]

The history of the bronze edition of Head of a Laughing Boy is exactly the same as that of Head of a Slave. The Rodin Museum holds two terracottas (inv. S.00197 et S.03903) and nineteen plasters (inv. S. 00908; S.03353; S.04167 à S.04180; S.06067) of Head of a Laughing Boy. Head of a Laughing Boy was cast in bronze for the first time by Alexis Rudier in 1925, commissioned by the Rodin Museum for Mastbaum; Rodin’s signature is on the three bronze examples that Alexis Rudier cast. The first belongs to the collections of the Rodin Museum in Paris (it came into the collections in 1925, inv. S.00759), the second belongs to the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia (it came into the collections in 1929, inv. F1929-7-5), and the third, which stayed in Camille Claudel’s family, is today in a private collection. Head of a Laughing Boy was re-attributed in a way very similar to that of Head of a Slave—through the discovery of a plaster with the signature “C. Claudel” on its neck.[29]

Head of a Slave and Head of a Laughing Boy, both in the collections of the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia, were the first two works by Claudel to enter, both in 1929, into American public collections.[30] Signed by Rodin and registered under his name in the museum’s inventory, they were thought to be posthumous casts. Now, thanks to additional facts that have become available, visitors to this museum can look at them differently and admire two works by Camille Claudel cast in 1925, thus during her lifetime, though beyond her control—that was in the hands of the Rodin Museum, as, by then, Claudel had been institutionalized for more than ten years.

It falls to Mathias Morhardt to conclude this discussion of the discovery of the true creator of Head of a Slave some 100 years after its creation. In his 1898 article on Claudel, he insisted upon the fact that the essential question is not one of attribution; it is, instead, the power and the value of the sculpture itself. “And so Mademoiselle Claudel became Rodin’s pupil, but the sole, essential thing is to make beautiful and noble sculpture. Time erases all signatures—but it saves the works that are worthy of it.”[31]

[1] 1990 LA CHAPELLE-PARIS, p. 105, n°10. The work was presented at the time as unfired clay.

[2] 2012 PARIS, p. 217-219.

[3] File on the work on the website of the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia:

[4] Georges Grappe’s predecessor, Léonce Bénédite, the first director of the Rodin Museum, died on May 12, 1925.

[5] On this plaster, an abattis is visible on the lower part of the face, and knife marks can be seen on the two cut surfaces. For a definition of the term abattis, see Marie-Thérèse Baudry, Sculpture méthode et vocabulaire, 4th edition, Centre des Monuments nationaux / Éditions du Patrimoine, Paris, 2000, p. 558.

[6] Paul Leroi, « Salon de 1886 », L'Art, 1886, p. 64-80.

[7] See the recent text on Camille Claudel’s time in Rodin’s studio by Clarisse Fava-Piz: “In Rodin’s Studio,” in 2023 CATALOGUE EXPOSITION MUSÉE CHICAGO-LOS ANGELES, p. 116-151.

[8] 1898 MORHARDT, p. 721

[9] 2008 CATALOGUE EXPOSITION MUSÉE MADRID-PARIS, p. 185.

[10] See 2005 CATALOGUE EXPOSITION MUSÉE QUEBEC-DETROIT-MARTIGNY, p. 66-67.

[11] See “Rodin and Camille Claudel: an impassioned dialogue” in : commissariat de Bruno Gaudichon, Anne Rivière, Camille Claudel. Au miroir d’un art nouveau, catalogue d’exposition [Roubaix, La Piscine-musée d’art et d’industrie André-Diligent, 8 novembre 2014 – 8 février 2015], Paris, Gallimard-Roubaix, La Piscine, 2014, p. 31-65. Clarisse Fava-Piz continues this investigation : see “In Rodin’s studio”, in 2023 CATALOGUE EXPOSITION MUSÉE CHICAGO-LOS ANGELES, p. 116-151.

[12] In 2007 CATALOGUE MUSÉE PARIS, v. I, p. 278, the attribution of the Head of a Slave to Camille Claudel had not yet been confirmed.

[13] 1976 CATALOGUE MUSÉE PHILADELPHIE, p. 606-612.

[14] Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, “La Porte de l’Enfer” (“The Gates of Hell”) in 2007 CATALOGUE MUSÉE PARIS, v. II, p. 607.

[15] See also 1976 CATALOGUE MUSÉE PHILADELPHIE, p. 606-612 and Clarisse Fava-Piz, “In Rodin’s Studio” in 2023 CATALOGUE EXPOSITION MUSÉE CHICAGO-LOS ANGELES, p. 120.

[16] Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, “Le Cri” (“The Cry”) in 2007 CATALOGUE MUSÉE PARIS, v. I, p. 278.

[17] This inability to distinguish between their works haunted Camille Claudel in her paranoiac delirium, as Danielle Arnoux explains. See 2011 ARNOUX, p. 68.

[18] For the opening of the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia, see Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, “Rodin and the Bronze” in 2007 CATALOGUE MUSÉE PARIS, p. 41-43. By the same author: « Le temps des musées (1917-1945) », in Laure de Margerie, La sculpture française une passion américaine, INHA / Snoeck, p. 417-422.

[19] Letter from V. Le Mancel (Velleda Le Mancel, the niece of Léonce Bénédite, the first director of the Rodin Museum) to Oscar M. Stern, September 7, 1925 (Paris, Archives of the Rodin Museum, United States Dossier PHILADELPHIA RODIN MUSEUM Letters 1924-1926).

[20] Paris, Archives of the Rodin Museum, United States Dossier PHILADELPHIA RODIN MUSEUM Letters 1924-1926.

[21] See purchase orders n°132 (August 27, 1925) for one cast and n°147 (December 1, 1925) for two casts (Paris, Archives of the Rodin Museum, Purchase orders, suppliers, from N°1 of January 12, 1921 to N°195 of July 1, 1926, R4-12 12 I 1921 / 1 VII 1926). The two bronzes of Head of a Slave that correspond to purchase order n°147 were delivered to the Rodin Museum on April 28, 1926, according to a document from the Rudier archives marked “4th Mastbaum order” (Paris Archives of the Rodin Museum, D73 year 1926).

[22] One was sent on the S.S. Liberty on January 23, 1926, and the two others were sent on the S.S. Wuakegan on June 1, 1926 (Paris, Archives of the Rodin Museum, United States Dossier PHILADELPHIA RODIN MUSEUM Letters 1924-1926).

[23]1926 CATALOGUE EXPOSITION AUTRE PHILADELPHIE, n°1662.

[24] Paris, Archives of the Rodin Museum, United States Dossier PHILADELPHIA RODIN MUSEUM Letters 1924-1926. Albert Rosenthal to Georges Grappe, September 17, 1926: “My dear Sir and Friend, I sent you photographs of the exhibition of the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia at the Sesqui-Centennial. I thought that they might interest and please you…You might also be pleased to know, my dear friend, that there is an increasing and now substantial interest in Rodin and that our gallery at the Sesqui-Centennial is currently one of the most popular.”

[25] A posthumous edition of this head was cast beginning in 1990 at the Coubertin foundry. See 2001 RIVIÈRE-GAUDICHON-GHANASSIA, p. 76, n°18.2; 2019 CRESSENT-PARIS, p. 313.

[26] For reconstructing the edition of the Head of a Slave by the founder Alexis Rudier on the basis of documents held in the archives of the Rodin Museum, I warmly thank Sandra Boujot, the archivist at that institution.

[27] The Rodin Museum in Paris does not have a copy in bronze of the Head of a Slave cast by either Alexis Rudier or Georges Rudier.

[28] The work is mentioned on p. 612. It was then in the collection of Mrs. Jefferson Dickson of Beverly Hills.

[29] See 2019 CRESSENT-PARIS, p. 330-331, n°42-1, repr.; 2023 CATALOGUE EXPOSITION MUSÉE CHICAGO-LOS ANGELES, p. 135, n°16, repr.

[30] On the presence of works by Camille Claudel in the United States, see Emerson Bowyer, “The Foreigner: Camille Claudel and the United States,” in 2023 CATALOGUE EXPOSITION MUSÉE CHICAGO-LOS ANGELES, p. 74-83.

[31] 1898 MORHARDT, p. 717.